Longer-Term Trends of U.S. Grocery Industry

To set the stage, first let’s walk through a few major long-term trends that impact the U.S. grocery industry.

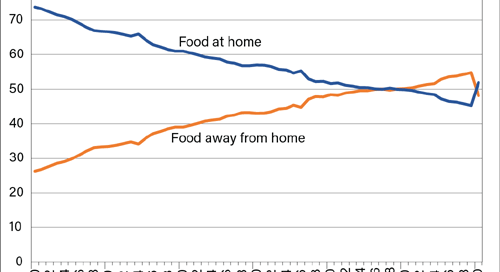

(1) Americans are eating more food away from home and less food at home. This is a very long-term trend, presumably driven by the rise in U.S. disposable incomes. I think it is safe to assume if you looked at this chart for a developing country, that although the trend may be the same, restaurant spend (“food away from home”) would be substantially lower (as a percent of total food expenditures). Less food at home has obvious negative implications for the grocery industry, however, there are certain factors that somewhat dampen/negate this negative depending on your place in the industry.

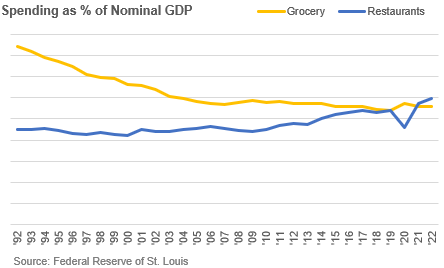

You can look at the above figures through a different lens by calculating each category as a percentage of GDP. Not surprisingly, over the past few decades, “Food at Home” has grown less quickly than GDP, while restaurant spending has grown slightly quicker than GDP.

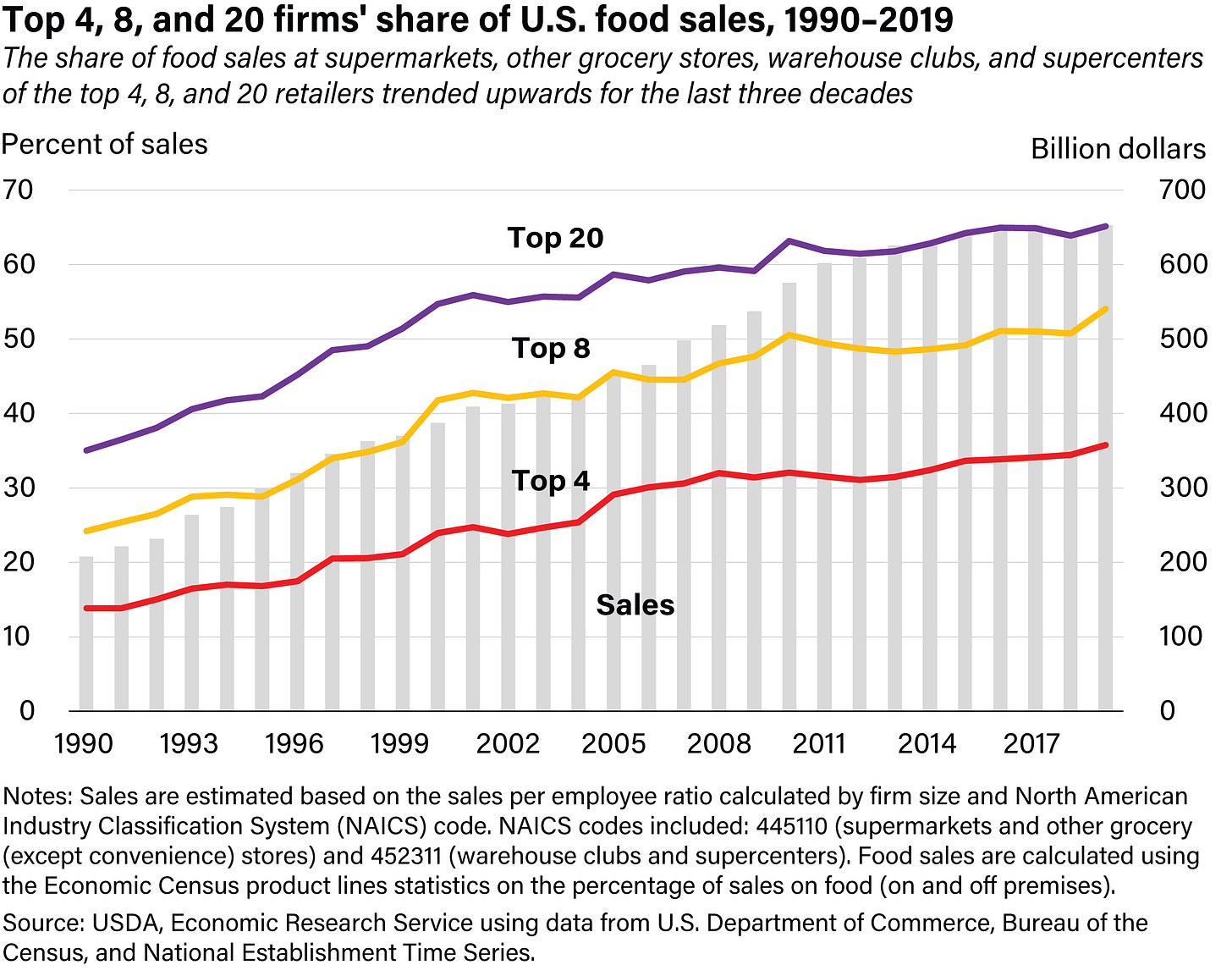

(2) Grocery sale consolidation continues to benefit the larger grocery chains. Another multi-decade trend that offsets, for the top grocery sellers at least, the increased propensity for Americans to consume food at restaurants. The grocery industry is a commoditized industry, where everyone is selling basically the same products. The lowest-price sellers will primarily “win” in this type of industry. And the main way to sell at a lower cost than your competitor in the grocery industry, is to have a scale advantage (discussed in more depth later), creating a lower unit cost structure. The scale advantage means the company can (1) utilize its large buying power to buy products at a lower unit cost than the competition, and (2) more sales per store mean your overhead costs as a percentage of your sales are less than the competition. The company can then price their products lower, giving some or all of the enhanced margin to their customers “in exchange” for higher sales.

Presumably this need for size, to be able to provide competitively-priced grocery’s, is the large driver behind the ever larger market share capture by the largest companies in the U.S. grocery industry. Scale matters in this industry tremendously.

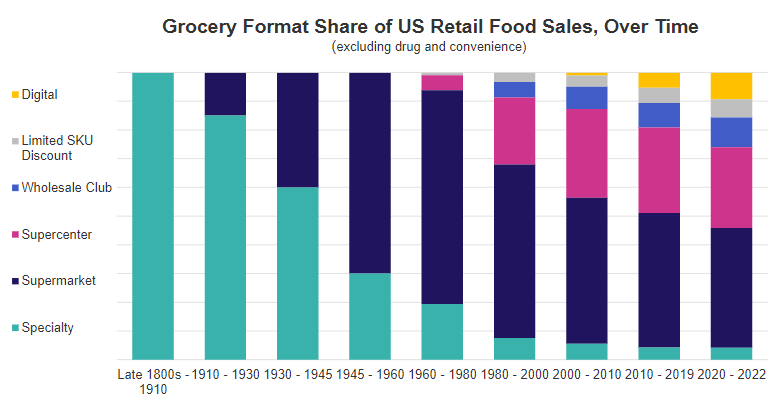

(3) Changing industry structure away from from purely traditional grocers. Although grocery sales continue to consolidate among the largest national players, they are not all pure grocery companies. Broader retailer supercenters (e.g., Walmart WMT 0.00%↑ ), wholesale clubs (e.g., Costco COST 0.00%↑ ), and dollar stores have gained increasingly relevance over time with U.S. consumers. Each offers its own additional advantage over the pure traditional grocer.

For example, a Walmart customer can choose to visit one of its supercenters for not only grocers but practically any consumer retail good they may need. This creates a huge convenience factor, combined with Walmart’s rock-bottom prices means U.S. consumers have flocked to it as their grocer of choice (see chart below - now largest grocery seller in U.S. at ~21% market share).

To summarize conclusions from these long-term trends:

Although grocery spend is increasing, it has been growing less quick than GDP as Americans allocate an increasing amount of their budget to restaurants or more generally, “food away from home”.

Consolidation among grocery sales is increasingly moving towards the largest competitors, likely due to their ability to offer the lowest prices.

Industry sales seem to be moving towards competitors that are not pure grocery stores.

What Grocery Customers Value

Before we discuss the industry in more detail, let’s discuss what may be obvious regarding what customers value.

Price

Although no person wants to overpay for goods, the lower the income, the more price becomes important. These ultra price conscious customers are the consumers who will drive across town to get a slightly better deal.

The warehouse clubs (e.g., Costco) benefit the more price conscious people act. These businesses can price lower than the competition due to their structural advantages.

Dollar stores cater to the ultra price-conscious consumer by generally offering smaller item sizes (i.e., less of the item per unit) and then typically selling at a higher per unit/ounce/etc. than most. Many dollar store customers only want a specific/smaller amount, as their monthly budgets do not allow them to stock up on an item, like a Costco offers.

Selection (quality, number of products per food category, etc.)

Most national grocery store chains offer, roughly, the same wide selection of grocery items. The major differing factor in selection, is in selling non-groceries or higher-quality groceries. Walmart fits the first category, selling a wide variety of general retail goods at their stores. While Whole Foods fit the second category, generally selling “higher-quality” grocery items that usually run 10-20% more expensive than the typical grocery store.

Convenience

The traditional supermarket (e.g., Kroger KR 0.00%↑ , Publix, etc.) will typically sell groceries at a slightly higher price per unit/ounce than you might find at a Costco but will normally have more locations, which make them more convenient for most customers within a town. For the time-constrained consumer, who does not need to be as price-conscious, many will choose to visit their neighborhood grocery store and be fine with paying a small “premium” on their groceries to do so.

The dollar stores also rely to some extent on this dynamic. For example, Dollar General’s DG 0.00%↑ core strategy is to locate their stores in rural areas where the closest Walmart is >40 miles away. This has allowed them to provide convenience to local consumers. However, as mentioned previously, even though their prices are lower than the mom-and-pop competitors they do not necessarily sell at the lowest per unit prices relative to the largest players.

“We went where they [Walmart] ain’t,” - David Perdue, Dollar General’s chief executive from 2003-2007.

Industry Economics & Competitive Advantages

The grocery industry is a commoditized industry selling non-exclusive items. Combined this with very low switching costs and you get an industry that competes primarily on price (i.e., no pricing power) and therefore minimal margins. However, the industry does have favorable asset turnover since groceries are bought frequently, which helps create low-to-no net working capital for some competitors. Let’s walk thru the economics of the industry in more detail.

Gross Margins

Purchasing Power

The size advantage is all important for two reasons - one of which is purchasing power. Larger/national grocery stores can demand better per unit pricing from suppliers. These suppliers agree to lower per unit pricing in exchange for more volume from that grocer. The much smaller grocery chains, cannot offer the same volume and therefore the supplier will demand higher pricing.

I know someone who works for a private, small-sized but fairly well-known, candy company. This person mentioned that the largest buyers (think Walmart, Costco), with their huge size, can dictate their pricing and terms unlike the rest of the competition. And the only companies receiving a lower per unit price than these large players are “close-out” companies (such as Ollie’s Bargain Outlet OLLI 0.00%↑ ), which get the very limited supply of left-over candy.

Again, size = purchasing power = “theoretically” higher gross margins. I say theoretical, cause the higher margin is mostly passed on to the customer via lower prices. And low prices, ultimately draw in incremental customers, while helping to retain current customers.

Private Label Brands

Private label brands are products owned/produced by the store selling them (e.g. Costco = Kirkland brand). Since the grocer is not buying the product from a 3rd party, they effectively eliminate the margin from that 3rd party.

Here’s a simple example. Product A is sold by Company X, a consumer packaged goods company. Product A costs Company X $10.00 to manufacture and then they sell it to a grocer for $13.00. Then Grocer Z marks Product A by 20% to $15.60.

Under the private label scenario, Grocer Z produces Product A itself. It costs $10.00 to manufacture, and they mark the product up by a higher margin of 30% to $13.00. Both Grocer Z and the consumer benefit as a higher margin is earned and the consumer gets a very similar product at a lower price.

Certain grocers have focused their business around the private label concept. Aldi and Trader Joe’s are the extreme examples, selling a substantial amount of their goods purely via private label (Aldi = ~90% private label and Trader Joe’s = ~60%). Although these companies do not have all the cost efficiencies of the larger wholesale clubs, their use of private label allows them to offer very competitively priced items.

Private label adoption has grown and certain stats show that once people switch to a private label product, they are unlikely to switch back. This progression helps grocer’s gross margins, although competitive pressures may dampen this gain if mostly everyone is achieving these gains too.

Alternative Profit Sources

Membership Fees

Membership fees, such as at Costco, create both additional loyalty and high-margin profits. From a financial sense, it also creates the beneficial dynamic of being paid for a service that is yet to be provided.

Advertising

Kroger has discussed this recently. Approximately 85% of Kroger’s top 500 keyword searches are for unbranded items (e.g., “cereal” not “Cheerios”). Kroger is beginning to allow their suppliers to advertise directly to their customers, creating an additional high-margin revenue stream for Kroger.

I’m no expert in this area but as digital advertising seems to be moving towards more privacy (e.g., new 3rd party cookie restrictions), the value of new advertising routes could increase. Especially, with most large grocers having loyalty programs and apps, which effectively means they have massive amounts of detailed customer/location level data, useful to any supplier.

Overhead (as % of revenue)

Scale

Not to beat this point into the ground but, again, scale matters also in terms of brining down overhead as a percentage of revenue. By selling more in your current infrastructure, a grocer creates additional margin by leveraging fixed costs that can be passed on to customers. This is simply done by generating increased sales in your current infrastructure or said another way, high sales per square foot and per employee. And what is the main way to generate a lot more sales than your grocery competitors? Low prices.

General Operational Efficiency

This goes without saying, if you can operate with less non-productive expenses your overhead will be lower, and thus margins higher. Some grocers structurally attempt to achieve this. Here’s some examples:

Aldi

Requires you to bag your own groceries, so they do not need to employ baggers.

Aldi’s cart policy requires customers to give them a quarter to “checkout” a cart, in order to ensure that the customer returns the cart. Again, this is so Aldi does not need to employ extra employees for cart returns.

Costco

“no-frills” warehouse style stores require less labor than the competition. Much of the merchandise is displayed on pallets and on racks above sales floor, which means no employees required to place/re-stock items neatly on a traditional grocery store shelf.

All these seemingly small structural cost efficiencies exist so that grocer/retailer can sell the goods at lower prices than the competition. As shown below, the warehouse clubs, with all their buying and operational efficiencies, allow them to price much lower than even Walmart, according to this Bank of America analysis.

Asset/Capital Intensity

Many of the larger players operate with zero or even negative net working capital. Meaning, suppliers are effectively funding a part of the company. Any inflationary or real unit growth in net working capital does not need to consume additional equity or debt dollars.

If customers are paying an annual membership fee than that advance fee is funding the business as well. Lowering the equity/debt capital required even further.

The way the large players achieve this low capital intensity is since they sell mainly to consumers, as opposed to business, allow them to turn their accounts receivable quickly (mainly credit card receivables). Combined with high inventory turnover means an accounts payable period of only ~30 days will create minimal-to-no working capital. Which is the typical financial dynamic that exists.

Even better, combined with the ability to lease their locations, creates a much less asset intensive business model than one might guess.

Resulting ROICs/ROAs/ROEs

The dual effect of generally lower margins and higher asset turnover, creates Return on Tangible Assets for the best players in the 7-10% range. Stable business models mean a decent amount of debt can be utilized and the low-to-no net working capital, means the equity required is small.

The end result is very acceptable Returns on Tangible Equity and Returns on Tangible Invested Capital. However, the trade-off is the industry is very mature in the U.S. with not much room to deploy capital at those high rates. This means a large portion of annual profits are deployed back to investors via dividends and share repurchases.

Industry Historical Financials

Below shows financials for a broad set of grocery stores plus multi-line retailers. This is mainly to provide the hard numbers behind the above qualitative discussion. Not completely apples-to-apples, since obviously some of the companies shown have a much greater mix of grocery sales (Kroger) than others (Target TGT 0.00%↑ ) but it should provide a recent historical overview of the group’s financials.

Note on data tables: If fiscal year was not equal to calendar year then I grouped it into the closest calendar year. Also, 2022 for some is equal to last-twelve-months.

Future Risks/Changes to the Industry

The one risk or future change I’ll mention here is Amazon and e-commerce competitors. In 2018, Kroger announced a partnership with Ocado, for Ocado to build their robotic-filled grocery fulfillment centers for Kroger in the U.S. Kroger is using this to expand, via e-commerce, into regions they do not have a presence. They expect these Customer Fulfillment Centers (CFC’s) to be profitable by Year 3 and in the longer-term, provide better unit economics than their stores.

Kroger, very understandably, praises these facts. However, if these facts are true, it seems like they could create potential risks for the industry. I am no expert in this area, but if these CFCs are really just combining Ocado’s automated fulfillment centers with some logistics abilities, I do not see why Amazon cannot do better. As these are the skills Amazon currently uses, extremely effectively, in non-grocery retail. And with Amazon’s motto of “your margin, is my opportunity”, a higher-margin e-commerce grocery solution seems dangerous the industries economics in the long-run (as Amazon would presumably compete those higher margins downward, pushing store margins downward too).

Again, I am no expert in this area, and all these are just some random thoughts. You can also argue that this threat might be far away, if it exists at all. However, I do think it is a topic to be further examined.

Final Thoughts

U.S. grocery industry is mature, slow/no growth industry, especially as U.S. consumers increasingly eat away from home.

The large national grocers do benefit as consumers grocery spend has been increasingly consolidating among the largest competitors.

Presumably, this spend consolidation, is because the largest competitors can offer the best prices. Scale matters in the grocery industry as it drives both increased buying power with suppliers and more sales per location - both acting to create a lower cost structure for the largest grocery competitors.

The wholesale clubs (Costco, BJs, Sams Club) have the lowest cost structures (as shown in the overhead/revenue table) and therefore typically can offer the lowest per unit prices. Others operate in certain niches that take advantage of customers preferences outside of price (convenience, selection).

I have printed it out. Looking forward to reading it.